$1 billion investment breaks boundaries

$1 billion promise

At a 1994 event, Wells Fargo’s EVP of Business Banking, and its highest ranking woman at the time, Terri Dial, was talking with a community partner about the obstacles to credit for women entrepreneurs. On the spot, Dial pledged Wells Fargo to lend $1 billion to women business owners.

When asked “Ok, who do we need to go to?” Dial responded “Nowhere, I can do that.” As she later reflected, “When you get to a position of power, you have to use it… it was an unbelievably freeing moment.”

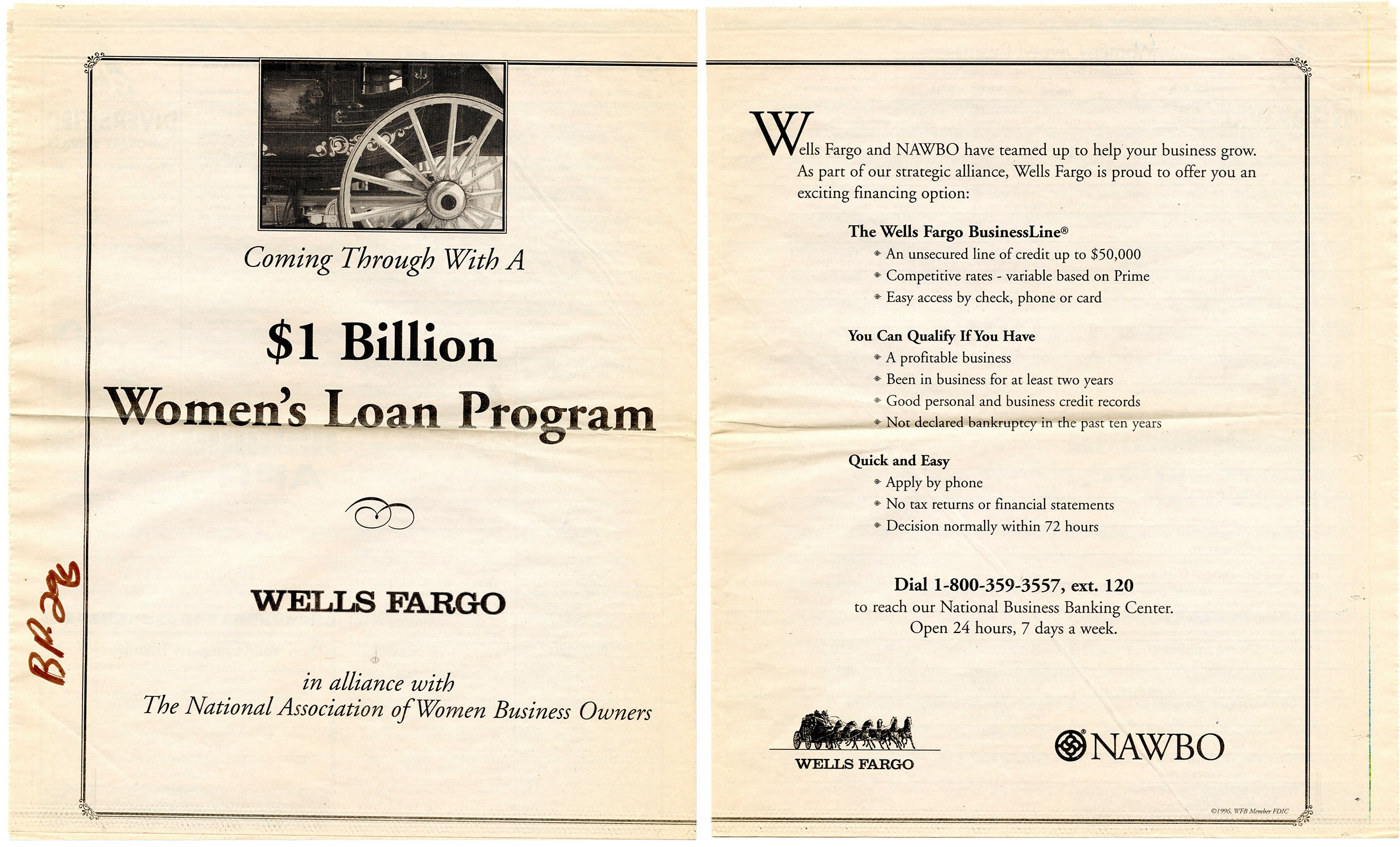

A few months later, Wells Fargo established a national education and outreach program to women-owned businesses with dedicated funding goals. In 1995, the bank announced its first commitment of $1 billion over three years.

This landmark program ─ the first of its kind at any bank ─ began a series of ambitious programs at Wells Fargo, and inspired similar programs throughout the financial services industry that continue today.

Overcoming a history of discrimination

The Women’s Loan Program sought to address generations of discrimination. While some banks provided personal and business loans to women in the past, many did not. Local laws and discriminatory policies barred women from the legal independence to sign for loans in their own name, often requiring the signatures of male relatives.

Following the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974, women gained the right to apply for personal credit in their own name. Loopholes remained for commercial borrowers, however, and women continued to be asked for male co-signers for loans.

One woman business owner explained her experience to Congress in 1988. When she applied for a business loan she did not have any living father, husband, or brother, so she had her 25-year-old son who worked for her company co-sign the loan.

Soon after, Congress passed the Women’s Business Ownership Act in 1988. It extended the same freedom from overt discrimination of the Equal Access to Credit to business loans. It also enacted a number of programs to support the growth of women-owned business, and collect data relating to women-owned businesses which became a trove of myth-busting statistics.

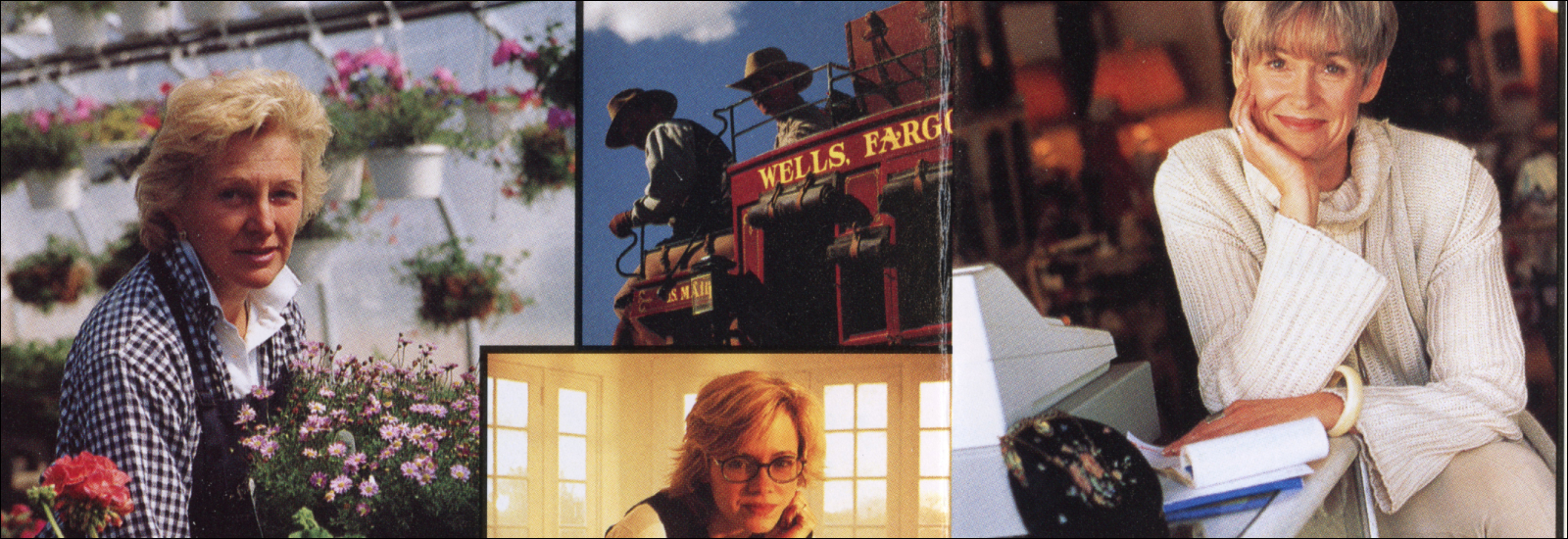

From 1987 to 1996, the number of women-owned businesses exploded from 4.5 million to 7.9 million. The growth impacted the larger economy as the number of employees working at a women-owned business rose from 6.6 million to 18.5 million, and the estimated revenue climbed from $681 billion to nearly $2.3 trillion.

Despite legal changes and the evidence of dramatic business growth, a 1994 survey revealed that more than half of women business owners continued to have no bank financing. Difficulty getting a business loan and past experiences led many women to conclude that bank financing was not an option. Women continued running businesses with money borrowed from friends and families, or taking out multiple credit cards as an informal line of credit.

Turning a pledge into a promise

As Terri Dial started developing a plan to bridge these financing gaps, she realized that the goal of providing access to credit for women-owned businesses required more than just a $1 billion pledge; it required outreach and removing systemic barriers.

Instead of expecting women with a history of distrust of financial institutions to come to Wells Fargo, the bank did a series of outreach campaigns working with community partners to spread the word.

The bank also streamlined the approval process with a one-page application and improved credit reviews. They assessed conventional lending guidelines and corrected requirements that caused unintended bias. For example, instead of counting it as a risk that a woman had multiple credit cards, they evaluated the history of debt and payments.

Many of these improvements had been slowly introduced since the early 1990s, when Wells Fargo started developing solutions for small businesses generally, but the improved processes had a huge impact on women business owners especially.

One customer had previously spent months trying to get a line of credit for her graphic design business. A mailing from Wells Fargo changed that, and in less than two weeks she had a line of credit. Another admitted that she had previously shied away from traditional financing, relying on friends and family to start her consultancy business in 1991. When she saw the loan program mentioned in a women business owners’ newsletter, she immediately called and was approved for $15,000 in three days.

By 1996 ─ and two years earlier than planned ─ Wells Fargo had met its first ambitious goal of $1 billion in lending to women business owners. About 75% of the loans were smaller than $25,000 reflecting the incredible scale of the lending program.

“We’re not doing it to be nice. We’re not doing it to be politically correct. We’re putting $10 billion behind women-owned businesses because women-owned businesses make money.” Wells Fargo ad, 1996

Since then, Wells Fargo has continued to set ever more ambitious goals, and has provided over $59 billion to women business owners from 1995 to 2019.

Continuing efforts to address historic disparity

Continued economic research showed the program’s impact, but also revealed additional weaknesses. Access to capital for women-owned businesses improved dramatically from 46% in 1996 of women reporting using bank financing rising to 52% within two years. But women business owners still had less available bank credit than their male counterparts, and people of color had a significantly harder time accessing capital.

Wells Fargo responded by applying successes from its women’s lending program to establish additional programs for Latino businesses (started 1997), African American entrepreneurs (1998), and Asian business owners (2002).

Today, Wells Fargo continues to develop innovative programs to connect women- and minority-owned businesses with funding.

Established in 2015, the Wells Fargo Diverse Community Capital (DCC) program provides funding and collaboration with CDFIs (Community Development Financial Institutions) that empower diverse small business owners with greater access to capital and technical assistance so they can grow and sustain local jobs.

In July 2020, Wells Fargo created the Open for Business Fund to provide capital and expertise for businesses hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. Since January 2021, the Open for Business Fund has deployed more than $84 million in philanthropic capital to Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), which has helped an estimated 16,000 struggling minority-owned small businesses and helped keep in place 50,000 small business jobs.