Wells Fargo’s bittersweet sacrifice of WWI

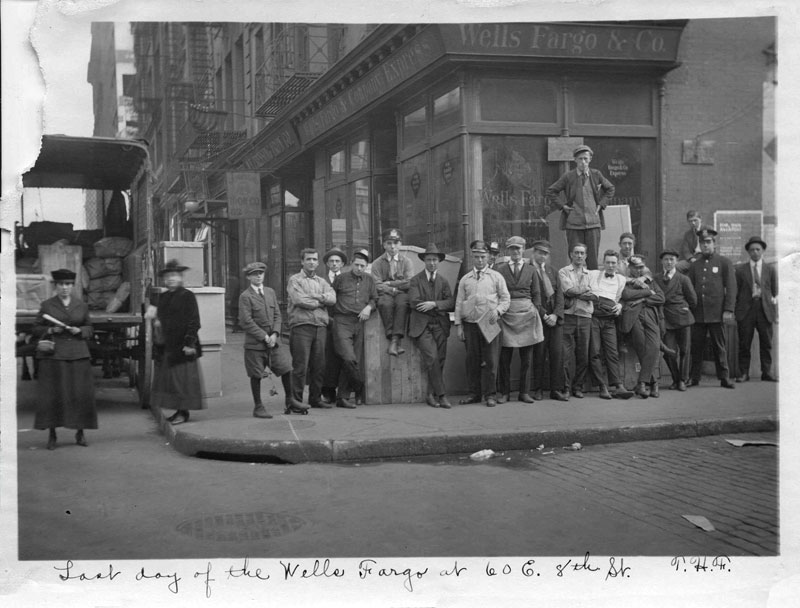

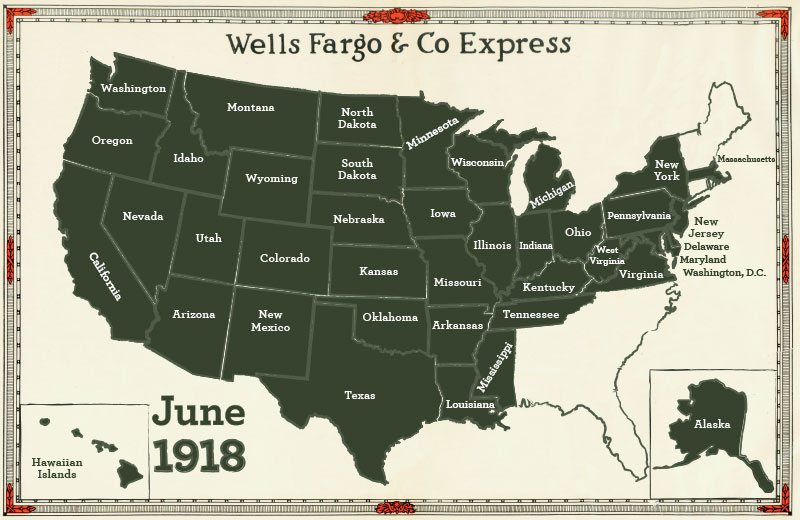

On June 30, 1918, staff at Wells Fargo & Co.’s express office at 60 E. 8th St. in New York City gathered outside on the sidewalk to take a nostalgic photograph. It was the last day any of them would work for Wells Fargo. At midnight, the federal government’s wartime merger of the major domestic express businesses would be complete.

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, it thrust itself into the War to End All Wars, a global conflict the world had never seen. The stakes of World War I were high, and it became very clear that the United States had a pressing problem to solve: getting much needed supplies and equipment to the soldiers who so urgently needed it.

Supporting the war effort

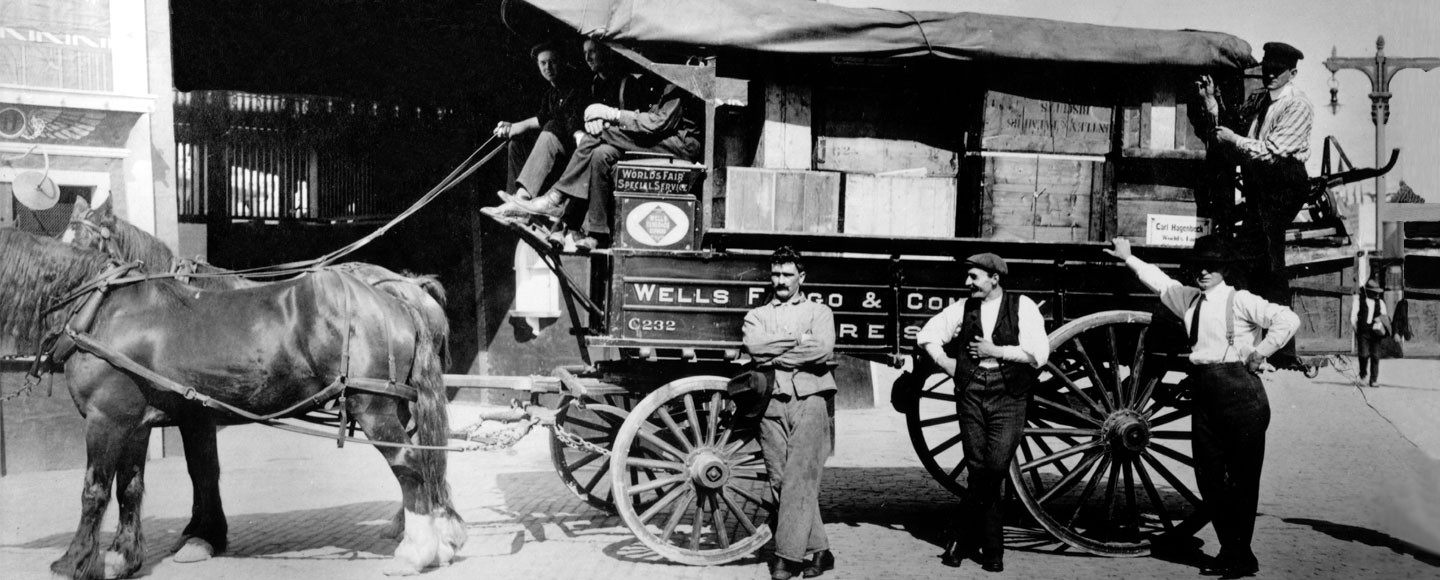

At the time, Wells Fargo had become a household name for service and dependability. Its express business moved packages, merchandise, and valuables that needed to travel quickly, safely, and with special handling. Although ending its express services was necessary to serve the greater needs of the country, it was also an emotional change for the thousands of men and women who worked for Wells Fargo.

In a book of memoirs, wagon driver Ollie Ziegler reflected back on his long career as a teamster in St. Louis and nostalgically remembered his time in Wells Fargo’s express service. He wrote, “My experiences have been many and varied. But today, as all this passes before me again, there is one period that I think of more than any other — that of my employment with the old Express Company. The men and boys I knew and worked with, the equipment, and many of the happenings are still green in my memory. And deep inside, always when it comes to mind, are the pangs of nostalgia for something that has passed and will never be again.”

On July 1, 1918, Wells Fargo turned over all its equipment and property used in its nationwide express business to American Railway Express, including thousands of wagons and motor trucks, horses, 175 refrigerated railcars, buildings, furnishings, and leases. American Railway Express attempted to quickly adopt a new identity, painting its fleet of wagons and motor trucks a drab battleship gray.

Many of Wells Fargo’s 35,000 express employees continued in the business as part of the American Railway Express workforce of 125,000. The experience in delivering packages quickly and reliably was essential during the war. Burns Caldwell, Wells Fargo & Co.’s president, chaired the board of the new American Railway Express company.

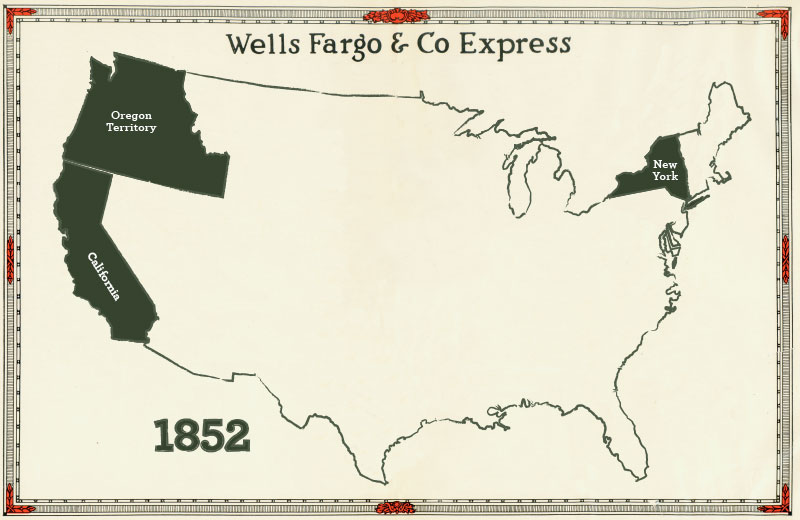

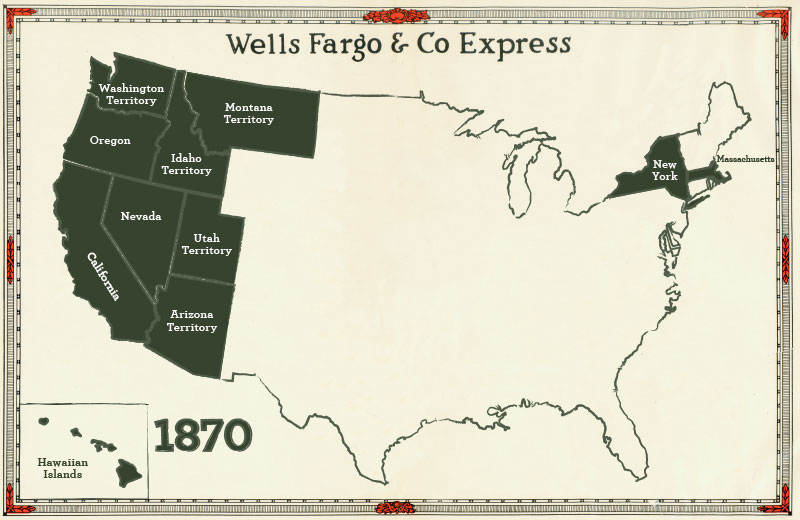

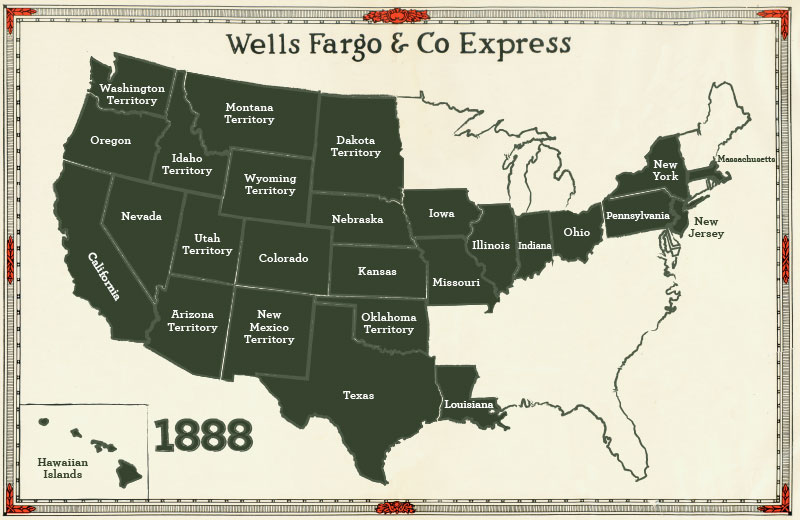

Wells Fargo’s express era

After the war

Still in the banking business

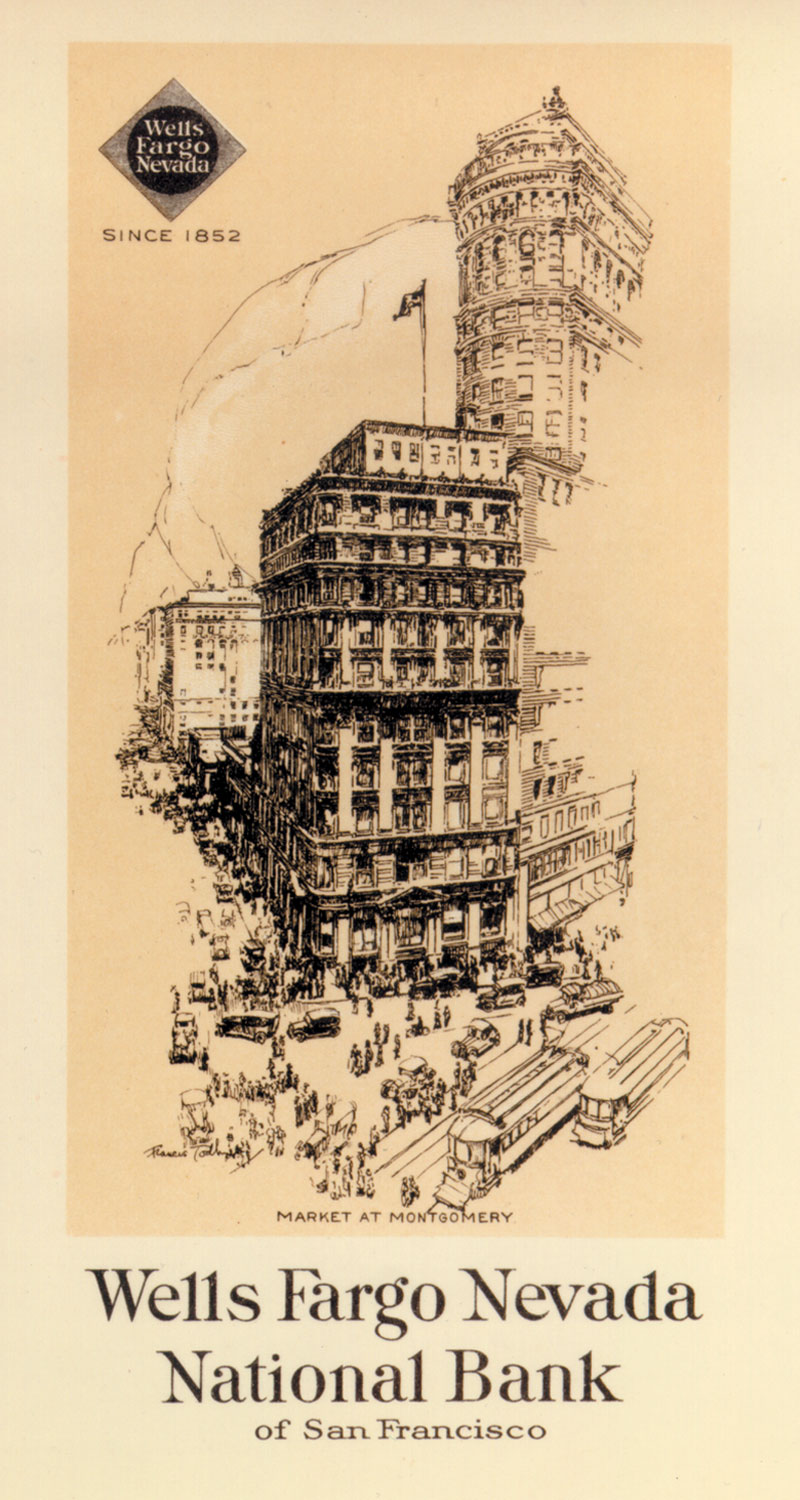

Even as a chapter closed on Wells Fargo’s history in the transportation business in 1918, the Wells Fargo name continued in banking as it had since 1852.

Wells Fargo & Co. had separated its banking and express businesses in 1905, when company president and railroad mogul Edward H. Harriman moved the headquarters of the express business to New York and sold off its San Francisco banking business to The Nevada Bank, under the leadership of California banker I.W. Hellman.

As the predecessor of today’s Wells Fargo Bank, it grew into a leading commercial bank on the Pacific Coast, and in recent decades the Wells Fargo name is once again known in financial services from coast to coast and around the world.

Following the Allied victory in World War I, pressure for a nationally coordinated shipping infrastructure eased, and the nation’s railroads returned to private ownership in 1920. Although there had been speculation that the wartime consolidation would later result in postwar re-privatization of express companies, Washington bureaucrats soon realized the nationwide express industry was a complex network that proved hard to untangle once combined. Whereas railroads had clearly identifiable assets like tracks, bridges, and routes, the express service was primarily an industry operating on existing railroad infrastructure.

And so, the American Railway Express continued on as a part of the daily commercial life of thousands of cities and towns. American Railway Express changed its name to Railway Express Agency in 1929 and remained in business until the mid-1970s, when the declining fortunes of railroads and rise of interstate highways and semi-trucks put it out of business for good.

Over its long history, Wells Fargo has seen many changes. But few changes altered the business so fast or so thoroughly as the end of the express era at the stroke of midnight on June 30, 1918.